Georges Perec

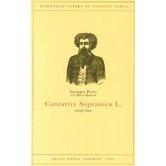

Georges Perec In 1974, Georges Perec, the French novelist of the Oulipo Group, wrote a hilarious pastiche of a scientific article about music: Experimental demonstration of the tomatotopic organization in the Soprano (Cantatrix sopranica L.). This parody is doubly relevant to neuroesthetics: its subject matter is a neuroesthetic study (how does throwing a tomato at a soprano affect her singing!), and the text itself is a masterpiece of language experimentation (pseudo-scientific article) by a virtuosic writer who was exposed to scientific literature when he was a librarian.

The comic effect in Cantatrix sopranica L. comes from the paradoxical distancing of the author (serious tone) from his and our emotions (laughter), and the use of abstruse vocabulary and syntax contrasting with the so-called straightforward scientific demonstration that they are meant to convey. At the same time, those who, like me, published or tried to publish articles in scientific journals, will recognize the mindset we are in when it comes to (re-re-re-)write and (re-re-re-)format a manuscript for submission, in a desperate attempt to fit in and please the reviewers. The language used in scientific articles has always puzzled me. At the same time, when I am in a good mood, I find the autonomous flow of technical words, the regular recurrence of specific terms of unclear significance that become more and more familiar throughout the text, the rhythm chopped up by references, and the unreadable figures supported by overloaded legends, almost endearing, if not poetic. Cristina Grasseni reported an unexpected appreciation of beauty through "skilled vision"; why not acknowledging that "skilled scientific writing" may also carry an inherent aesthetic value?

Yet I find the format of scientific writing very limiting in terms of creativity. In 2012, Phillip Prager, who spoke at the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics, suggested in his article "Making an Art of Creativity: The Cognitive Science of Duchamp and Dada" (Creativity Research Journal), that scientists are less resistant than artists to the idea of creativity as a "combinatorial process" that can be the result of chance: "seemingly incompatible concepts are blended into surprising new meanings, ‘‘a cut and paste process’’ in which ‘‘two concepts or complex mental structures are somehow combined to produce a new structure, with its own new unity (...) or ‘‘conceptual combination’’". Prager refers to scientific discoveries that date mostly from last Century (ex: unexpected discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928). I wonder if "chance" is still embraced today as a factor of creativity in scientific research, especially in academia? Where is the space for creativity, chance and combinatorial process in scientific articles?

Similarly, this question applies to scientific grant applications: guidelines suggest that they be strongly "hypothesis driven", with a clearly defined "aim", and preliminary data (supporting the hypothesis) are a pre-requisite. More specifically, the NIH recommends, when it comes to designing a project for RO1 grants (classic research grants for principal autonomous investigators): "Be innovative, but be wary" or "Since innovation is a review criterion, you want to think outside of the box—but not too far". According to the NIH, innovation is a slight expansion of the "known" towards the "unknown" (see picture below). There is no space for chance, and barely for risk.

So I am wondering and hoping: could neuroesthetic research (and emerging literature) be innovative and free itself from the sole constraints of academic standards? Could the emerging neuroesthetic literature be more open to chance? Wouldn't it foster creativity in the field? I hope so, but there may be a long way to go: Phillip Prager told me he was not able to publish his paper in an "art history" journal, while a more "scientific journal" accepted it right away. Still, when I read his article, I did not find it really... scientific (nor do I think that Creativity Research Journal can be considered a pure scientific journal)! Regardless, I found his article absolutely fascinating and relevant to both science and the history of art.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed