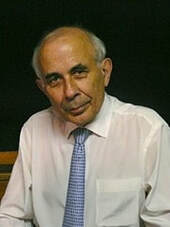

Semir Zeki

Semir Zeki I met Semir Zeki to talk about neuroesthetics on a rainy Tuesday of March 2019, in his office at the University College London. As I was getting ready for the interview, I wondered what the working environment of a neuroestheticist looked like. Semir Zeki set the tone when he emailed me: "This is a secure area and the best is to go to the Anatomy Entrance (NOT the Darwin Building entrance)." That said it all! Neuroesthetics was about science and anatomy. Therefore, on my way there, I made sure to put my neurology hat on, and braced myself for a potentially dry discussion about how tiny gray matter areas in the frontal lobe process our perception of visual beauty. I was both relieved and delighted when the discussion took another turn, rapidly bridging out to Renaissance paintings, Mondrian or Agnes Martin, and how these art topics interface with neurobiology.

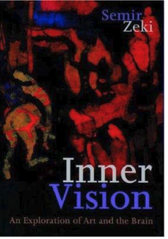

Semir Zeki defined the term neuroesthetics over two decades ago. He shared his approach in his book, "Inner Vision, an Exploration of Art and the Brain", published in 1999. In 2001, he summarized his conception of neuroesthetics: "Visual art obeys the laws of the visual brain, and thus reveals these laws to us" (Artistic creativity and the brain, Science 2001). I asked him how he defines neuroesthetics today, what his interactions with the art world are, and which future directions he envisions in the field.

Semir Zeki insisted that his work is primarily focused on the brain, more precisely on how the brain functions in "the common man" (as opposed to the artist's brain). He also confirmed that his scientific research, which remains question driven, is often derived from observations originally made by art historians or philosophers. "We aim at understanding the brain mechanisms underlying the perception of beauty, rather than asking what beauty is." he told me.

It was a pleasure and a real honor to discuss with Semir Zeki, father of contemporary neuroesthetics, and a true "Renaissance Man", in the most noble and inspiring way.

These are edited excerpts from our conversation.

Semir Zeki defined the term neuroesthetics over two decades ago. He shared his approach in his book, "Inner Vision, an Exploration of Art and the Brain", published in 1999. In 2001, he summarized his conception of neuroesthetics: "Visual art obeys the laws of the visual brain, and thus reveals these laws to us" (Artistic creativity and the brain, Science 2001). I asked him how he defines neuroesthetics today, what his interactions with the art world are, and which future directions he envisions in the field.

Semir Zeki insisted that his work is primarily focused on the brain, more precisely on how the brain functions in "the common man" (as opposed to the artist's brain). He also confirmed that his scientific research, which remains question driven, is often derived from observations originally made by art historians or philosophers. "We aim at understanding the brain mechanisms underlying the perception of beauty, rather than asking what beauty is." he told me.

It was a pleasure and a real honor to discuss with Semir Zeki, father of contemporary neuroesthetics, and a true "Renaissance Man", in the most noble and inspiring way.

These are edited excerpts from our conversation.

How do you define neuroesthetics?

Neuroesthetics is a field designed to study the brain. For example: what are the brain systems engaged when you create a work of art, when you experience a work of art, when you experience beauty, or when you experience other emotions that are linked to beauty, such as love or desire?

By opposition, neuroesthetics does not address topics like beauty the way philosophers do. This notion is very important to me, even though there are a lot of art historians and philosophers specialized in esthetics who are resistant to my approach.

Can you talk more about your neuroesthetic approach of beauty?

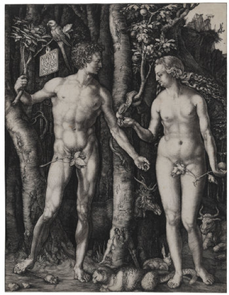

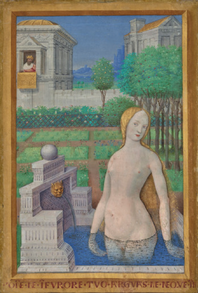

I believe that the fields of beauty, love and desire, are all linked. This morning I went to the exhibition "The Renaissance Nude", at the Royal Academy of Art in London (Figures 1 and 2). These beautiful paintings were all about desire, sexuality and love, combined.

I am aware that philosophers and art historians have been debating these questions for a long time. I don't dismiss their work. I say they have something to contribute to us. Let's use what they have to contribute.

For example, I share with them an interest in beauty. My approach is to study the brain mechanisms that are engaged when you experience beauty. From a neuroesthetic standpoint, however, the topic is not only about beauty itself, it is larger than that. For example, the brain mechanisms engaged when you experience beauty are related to the ones engaged when you perceive color, faces, or movement. It is the same question.

For that reason, I think that art is not necessarily equal to beauty. A lot of artists started distinguishing art from beauty after Marcel Duchamp's Urinal [Fountain, sculpture, by Marcel Duchamp (1917) is considered one of the most influential artwork of the 20th century, at the origin of conceptual art. Duchamp aimed at "de-deifying" the artist] (Figure 3). Some philosophers, however, would argue that one can't distinguish art from beauty.

The question of beauty is related to the question of judgement: I think you can distinguish esthetic judgement from perceptual judgement. In esthetic judgement, you may ask: which shape is the most beautiful? While in perceptual judgement, the question could be: which shape is the largest? My question is: do these two types of judgements follow the same, or different pathways?

Please note that most of the questions I am interested in, arise from the thought of philosophers in esthetics: what are the distinct brain mechanisms involved when you experience something you find sublime, versus something you find "just beautiful"? What are the brain mechanisms involved when you make a decision with regard to beauty or desire? This shows you that the scope of the field is very wide. It is not limited to just studying beauty. It includes everything that is allied to beauty.

Neuroesthetics is a field designed to study the brain. For example: what are the brain systems engaged when you create a work of art, when you experience a work of art, when you experience beauty, or when you experience other emotions that are linked to beauty, such as love or desire?

By opposition, neuroesthetics does not address topics like beauty the way philosophers do. This notion is very important to me, even though there are a lot of art historians and philosophers specialized in esthetics who are resistant to my approach.

Can you talk more about your neuroesthetic approach of beauty?

I believe that the fields of beauty, love and desire, are all linked. This morning I went to the exhibition "The Renaissance Nude", at the Royal Academy of Art in London (Figures 1 and 2). These beautiful paintings were all about desire, sexuality and love, combined.

I am aware that philosophers and art historians have been debating these questions for a long time. I don't dismiss their work. I say they have something to contribute to us. Let's use what they have to contribute.

For example, I share with them an interest in beauty. My approach is to study the brain mechanisms that are engaged when you experience beauty. From a neuroesthetic standpoint, however, the topic is not only about beauty itself, it is larger than that. For example, the brain mechanisms engaged when you experience beauty are related to the ones engaged when you perceive color, faces, or movement. It is the same question.

For that reason, I think that art is not necessarily equal to beauty. A lot of artists started distinguishing art from beauty after Marcel Duchamp's Urinal [Fountain, sculpture, by Marcel Duchamp (1917) is considered one of the most influential artwork of the 20th century, at the origin of conceptual art. Duchamp aimed at "de-deifying" the artist] (Figure 3). Some philosophers, however, would argue that one can't distinguish art from beauty.

The question of beauty is related to the question of judgement: I think you can distinguish esthetic judgement from perceptual judgement. In esthetic judgement, you may ask: which shape is the most beautiful? While in perceptual judgement, the question could be: which shape is the largest? My question is: do these two types of judgements follow the same, or different pathways?

Please note that most of the questions I am interested in, arise from the thought of philosophers in esthetics: what are the distinct brain mechanisms involved when you experience something you find sublime, versus something you find "just beautiful"? What are the brain mechanisms involved when you make a decision with regard to beauty or desire? This shows you that the scope of the field is very wide. It is not limited to just studying beauty. It includes everything that is allied to beauty.

Can you tell us about the creation of the field of neuroesthetics?

Neuroesthetics embodies the notion of interdisciplinarity. The field arose organically from the 1980s onwards. I created the term "Neuroesthetics" in December of 1995. I was giving The Woodhull Lecture at the Royal Institution in London. I talked about specialized functions of the brain (color vision, form vision, motion vision), and about brain and beauty in art. This is how the term was created (see "Inner Vision, an Exploration of Art and the Brain").

How big is the neuroesthetics community?

There are two categories of people specialized in neuroesthetics. The ones that are officially "out of the closet", who say they work in the field. And the ones who contribute to neuroesthetics without calling themselves "neuroestheticists". For example, researchers studying decision making, or sexual desire, contribute to the field of neuroesthetics, even though that was not their original intention. The field of neuroesthetics is continuously expanding.

The art scene and the history of art are very different in the UK compared with America. How do you think this influences your work?

Art may be more sophisticated here in the UK, but America is more hospitable to new ideas. So in a way, I would love to combine the two. I have a fond memory of the International Neuroesthetics Conference held by the Minerva Foundation in Berkeley, that I co-created with my friend Elvin Marg. I am sorry that this project is on hold.

Do you often derive your research questions from artists?

Yes, I have plenty of examples.

The English art critique Clive Bell (Figure 4) suggested that certain visual elements trigger our experience of beauty, and we all share this [In his book Art (1914), Bell [1881-1964] claims that certain forms, lines and colors trigger esthetic emotions that are common across cultures and unrelated to object identity. He was therefore a defender of abstract art.]

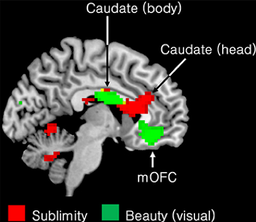

From Bell's philosophy, we derived our neuroesthetic study about the common brain pathways engaged when we experience something as beautiful (Figure 5, , see this article). We extended our analysis to both visual and musical stimuli. The perception of visual or musical beauty starts with specific sensory inputs [visual or auditory], but shares a common pathway associated with the feeling of beauty itself, located in the medial orbito frontal cortex.

We later extended our analysis even further, to another kind of beauty: the beauty of mathematics. This was based in the evocation of mathematical beauty by Bertrand Russel and Herman Weyl. [Russel [1872-1970] was a British mathematician, philosopher and Nobel laureate. In The Study of Mathematics, published in 1919, he wrote: "Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty—a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture". Weyl [1885-1955] was an influential German mathematician and philosopher. He viewed the field of mathematics as an organic whole rather than a series of individual subjects. He said : “My work always tried to unite the truth with the beautiful, but when I had to choose one or the other, I usually chose the beautiful.”] In this study, we found that the brain mechanisms underlying the appreciation of mathematical beauty are similar to the ones involved when visual stimuli are perceived as beautiful [The study shows that the experience of mathematical beauty, like the experience of musical or visual beauty, correlates with a similar activity the medial orbito frontal cortex of the brain]. This paper about mathematical beauty ended up being of huge general interest since, as of today, its online version has been viewed over 160,000 times! Interestingly, despite the eventual general interest, the manuscript was rejected a few times by other journals before its final publication.

Do you think this is because editors were unsure how to categorize it?

Well, this is exactly the problem. Still, the publication of this paper allowed some closeted mathematicians to talk more openly about the beauty of mathematics. Beauty is a very important component of mathematics.

Do you have other examples of questions derived from the field of art or philosophy?

Another example of a question derived from philosophers is the question of the brain mechanisms engaged in the appreciation of beauty versus the sublime: this study was derived from the writings of Edmund Burke, Immanuel Kant and Arthur Schopenhauer about the notion of sublime versus beauty. [The sublime may be described as the quality of ultimate greatness (Figure 6). Edmund Burke [1729-1787] was an Irish statesman and philosopher. In A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1756), Burke says that sublimity and beauty are mutually exclusive, both able to trigger pleasure, even though sublimity may be associated with horror. Kant [1724-1804] was a German philosopher. In Critique of Judgment (1790), Kant writes that beauty "is connected with the form of the object", having "boundaries", and relates to "Understanding", while the sublime "is to be found in a formless object", represented by a "boundlessness", and belongs to "Reason". Schopenhauer [1788-1860] was a German philosopher. In The World as Will and Representation (1818), he proposes a gradient of transition from the "Feeling of Beauty" (pleasure from the mere perception of an object) to the "Fullest Feeling of Sublime" (pleasure from knowledge of the observer's nothingness and oneness with Nature).]

Our neuroesthetic analysis confirmed that, indeed, the perception of sublimity is associated with a brain activation pattern distinct from the one associated with the perception of beauty (Figure 5).

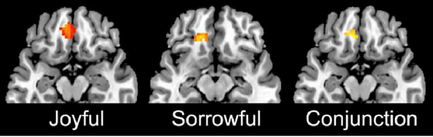

The topic of beauty versus sublimity is related to the notion that beauty can be derived equally from sorrow and from joy. Interestingly, even though these are two opposite emotions, both sorrow and joy are associated with the activation of the brain region involved in the perception of beauty (the medial orbito frontal cortex) (Figure 7, see this article).

You are saying that opposite emotions may be associated with a common brain pathway (in this case the one involved in the perception of beauty). On the other hand, we know that some emotional manifestations that seem identical may engage distinct brain mechanisms. For example, uncontrollable laughter can be triggered by the stimulation of a specific part of the subthalamic area in cases of deep brain stimulation, or by activation of totally distinct temporal, frontal or hypothalamic areas in gelastic epileptic seizures.

Yes. Similarly, visual stimuli associated with beauty can be diverse. Philosophers of esthetics, and art critics have asked for a long time what is common to all the things we experience as beautiful. Clive Bell wondered what were the commonalities between the windows of the Chartres cathedral [1220], a masterpiece by Nicolas Poussin [1594-1665] or Piero della Francesca [1416-1492]. But he never gave an answer.

Neuroesthetics can give an answer, and it is a neurobiological answer: ultimately, everything that you experience as beautiful [but not sublime] correlates with activity in the medial orbito frontal cortex (Figure 5). The correlation has been demonstrated. What remains to be demonstrated, though, is how you get there. This is a good example for the future directions in neuroesthetics.

What do you want to tell art critics, art historians or philosophers that you perceive as "neurophobic"?

The group of neurophobics is a small group, but it has been remarkably vocal. I would reciprocate by telling them: "you may hate us, but we love you!" As a neuroestheticist, I am inspired by questions asked by art historians, or art critics. I am also extremely interested in artists and the interest has been reciprocal. I regularly discuss at length with artists about topics of common interest. I learn a lot from collaborating with artists and art institutions (schools, museums).

You described the term "neurophobia". I am curious to know if you ever observed the reverse phenomenon, that I would call "artphobia", among scientists?

Not at all! The scientific community I know has been very hospitable to neuroesthetics. For scientists, the question is what is important. I have always had a lot of support from the scientific community to address scientific questions related to neuroesthetics.

Do you have artists in your lab?

Absolutely! I have students from the arts faculty, and a PhD student studying philosophy.

We are really very open, as long as one understands that my laboratory is a scientific one. All collaborations are welcome, as long as they help us understand the brain: we aim at understanding the brain mechanisms underlying the perception of beauty, rather than asking what beauty is.

What would you expect from an ideal neuroesthetics conference?

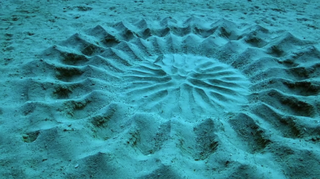

My current topics of interest are questions related to desire, beauty and love. I would invite presenters with various backgrounds, as long as their knowledge contribute to answering these questions. For example, in 2015, I organized a meeting called "The Science of Beauty" at the Royal Society in Edinburgh. Sir Roger Penrose gave a beautiful talk on the role of Art in Mathematics and Sir David Attenborough spoke about the sense of beauty in pufferfish (see BBC documentary). Did you know that these pufferfish create fantastic visual patterns in the sand on the sea floor to attract females? They create these patterns in a carefully balanced way, coordinated with the tide. We debated about what appears to these animals to be a desirable experience, and the fact that, still, we aren't able to comment about their perception of beauty.

You are saying that opposite emotions may be associated with a common brain pathway (in this case the one involved in the perception of beauty). On the other hand, we know that some emotional manifestations that seem identical may engage distinct brain mechanisms. For example, uncontrollable laughter can be triggered by the stimulation of a specific part of the subthalamic area in cases of deep brain stimulation, or by activation of totally distinct temporal, frontal or hypothalamic areas in gelastic epileptic seizures.

Yes. Similarly, visual stimuli associated with beauty can be diverse. Philosophers of esthetics, and art critics have asked for a long time what is common to all the things we experience as beautiful. Clive Bell wondered what were the commonalities between the windows of the Chartres cathedral [1220], a masterpiece by Nicolas Poussin [1594-1665] or Piero della Francesca [1416-1492]. But he never gave an answer.

Neuroesthetics can give an answer, and it is a neurobiological answer: ultimately, everything that you experience as beautiful [but not sublime] correlates with activity in the medial orbito frontal cortex (Figure 5). The correlation has been demonstrated. What remains to be demonstrated, though, is how you get there. This is a good example for the future directions in neuroesthetics.

What do you want to tell art critics, art historians or philosophers that you perceive as "neurophobic"?

The group of neurophobics is a small group, but it has been remarkably vocal. I would reciprocate by telling them: "you may hate us, but we love you!" As a neuroestheticist, I am inspired by questions asked by art historians, or art critics. I am also extremely interested in artists and the interest has been reciprocal. I regularly discuss at length with artists about topics of common interest. I learn a lot from collaborating with artists and art institutions (schools, museums).

You described the term "neurophobia". I am curious to know if you ever observed the reverse phenomenon, that I would call "artphobia", among scientists?

Not at all! The scientific community I know has been very hospitable to neuroesthetics. For scientists, the question is what is important. I have always had a lot of support from the scientific community to address scientific questions related to neuroesthetics.

Do you have artists in your lab?

Absolutely! I have students from the arts faculty, and a PhD student studying philosophy.

We are really very open, as long as one understands that my laboratory is a scientific one. All collaborations are welcome, as long as they help us understand the brain: we aim at understanding the brain mechanisms underlying the perception of beauty, rather than asking what beauty is.

What would you expect from an ideal neuroesthetics conference?

My current topics of interest are questions related to desire, beauty and love. I would invite presenters with various backgrounds, as long as their knowledge contribute to answering these questions. For example, in 2015, I organized a meeting called "The Science of Beauty" at the Royal Society in Edinburgh. Sir Roger Penrose gave a beautiful talk on the role of Art in Mathematics and Sir David Attenborough spoke about the sense of beauty in pufferfish (see BBC documentary). Did you know that these pufferfish create fantastic visual patterns in the sand on the sea floor to attract females? They create these patterns in a carefully balanced way, coordinated with the tide. We debated about what appears to these animals to be a desirable experience, and the fact that, still, we aren't able to comment about their perception of beauty.

I am interested in the subject of object identity. This is a relevant topic for artists (ex: representational versus abstract paintings) and art historians (ex: understanding the birth of cubism, minimalism). Could you comment on the brain mechanisms that are engaged when looking at highly representational images, versus images with less identifiable subject matter?

This is a very interesting question. As I wrote in my book, in 1999 [Inner Vision: An Exploration of Art and the Brain, by Semir Zeki], Picasso and Braque faced the question of how to maintain object identity in spite of the variations in the distance, multiple points of view etc.. In neurobiology, we call this the problem of form constancy.

Piet Mondrian, who was very much seduced by both early analytical and late cubism, said that cubists failed at determining the common constituents of all forms, because it was technically difficult for them to represent different points of view on a single canvas. Instead, he suggested that vertical and horizontal lines were the common constituents of all shapes (Figure 8A).

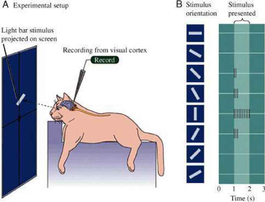

As a neuroestheticist, I think that Mondrian was wrong, too, and here is why: at some point, as Mondrian felt it instinctively, neurobiologists came to believe that we construct all forms from orientation selective cells [Orientation selective cells belong to our neuro-ophthalmologic system and were discovered by Hubel and Wiesel in 1959 (laureates of the 1981 Nobel Prize). These are cells that perceive lines oriented in a specific direction. The majority of orientation selective cells perceive vertical lines only, or horizontal lines only (Figure 9, as explained in this article).] I find this neurobiologist approach as reductionist as Mondrian's approach. Instead, I think there are other pathways that coexist and sometimes precede the perception of our visual environment by orientation selective cells. For example, the brain has got a template for recognizing faces. This pathway of face recognition is essential, and exists independently on line or orientation selective perception: babies who are 3-4 hours old already orient preferably toward faces. So, the reality of how we perceive a face is more complex than through lines oriented in a certain way.

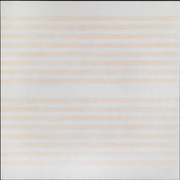

Talking about lines, Agnes Martin, who spent years painting horizontal and vertical lines only, felt that they were the essence of beauty: "Take beauty: it's a very mysterious thing, isn't it? (...) My paintings are (...) just horizontal lines. There's not any hint of nature. And still everybody responds, I think." (interview by Joan Simon, in Taos, 1995). As if these lines, whether they satisfied the over-representation of the corresponding orientation selective cells, or they were related to some kind of geometric perfection, activated the same common pathway associated with beauty as perceived from visual stimuli or mathematics. What does this inspire you?

It seems that Mondrian perceived vertical and horizontal lines as pure beauty, in a way similar to Agnes Martin's (Figure 8B).

That being said, we are now talking about the perception of beauty through the eyes of painters. I would like to emphasize again that neuroesthetics is not interested in the artist, composer, or painter; it is not interested in the art historian. Neuroesthetics is interested in "the common man". Neuroesthetics assumes that all humans have the capacity to experience beauty, but what each one experiences as beautiful is different [beauty is subjective]. We are so much interested in the common mechanisms of the perception of beauty, that, in our studies, we exclude painters, artists and "knowledgeable people". This idea also comes from Clive Bell: he said that if you want to know about esthetic emotion, don't ask an artist for he knows too much! Ask the "savages", the infants!

I would like to switch to the topic of future directions in neuroesthetics. Edsger W. Dijkstra (1930-2002), Dutch early pioneer in computing science, once said: “The question of whether a computer can think is no more interesting than the question of whether a submarine can swim.”. Would you like to comment on this, and, in general, on the question of whether a computer can produce or appreciate art?

I go along with this quote! I think a computer may be able to produce art, I don t think it can appreciate art. However, I am very hesitant to talk about computers in general. I am very suspicious of these deep learning programs, artificial intelligence etc... They can certainly do a lot of things but I am not sure they can appreciate beauty; and if they do, what I know is: this won't happen in my life time! And there is something that will always be challenging to model: "the soul".

[In itallic]: notes and references added by me

RSS Feed

RSS Feed