Visually enabled geographical reasoning

Alan M. MacEachren

Alan M. MacEachren What I learned from Alan is that there is such a thing as geovisual analytics: it means creating maps, that not only show you where places are, but help you think and integrate other types of information (where, when, what) in a visual interface. This is about facilitating KNOWING from SEEING.

As Alan showed it, this can be very useful when dealing with acute war or humanitarian crisis, where lots of information of diverse nature, format and source need to be rapidly and smartly processed in order to be presented in a visually integrated and useful way. A visually accessible summary can come in handy in specific situations (see this short video presentation of SensePlace2 a as an example).

This is about applying design, geography, and computer science to efficient understanding of complex situations, using a visual interface. Could we apply the same method to the headache of neuroesthetics? Could we have a visualization of the brain functional anatomy (topographic map of the brain), built on our current knowledge, integrating the inputs from all the other cross disciplines that relate more or less to the topic (anthropology, design, art etc...)? We could call that "the visual map", or "the artistic map", or the "seeing and knowing map".

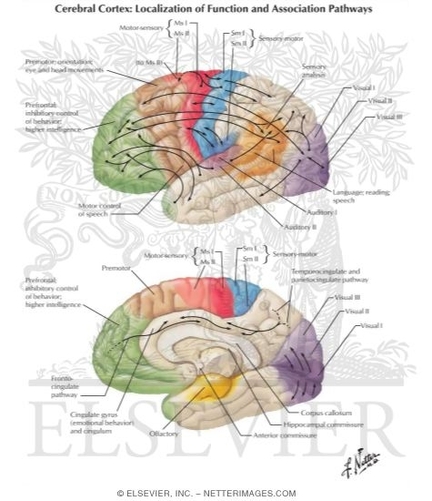

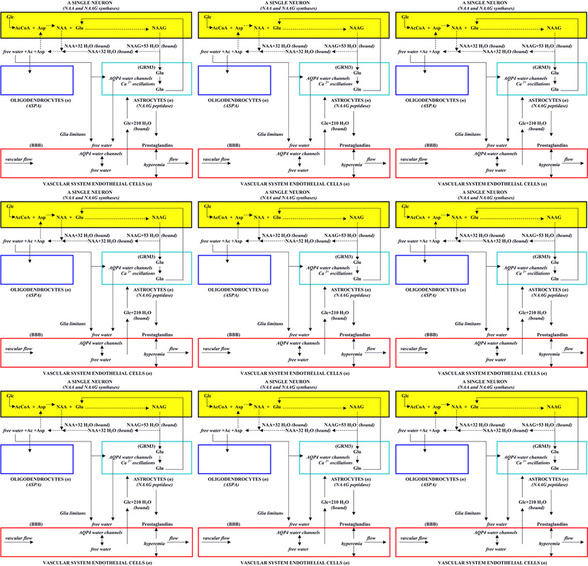

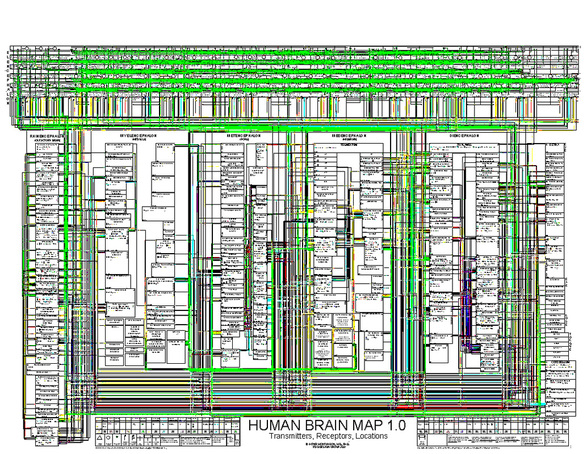

When I learned Neurology in the early 1990s, we used the term "boxology" to pejoratively qualify a visual way to understand and explain how the central nervous system works. Below are three "boxologic attempts" to represent the complexity of brain functioning (pictures 1-3). Which one do you find the most efficient? Likely the first one, which is simplified and where there is a map (of the brain) to support your understanding. At the same time it lacks the biological or cellular levels (picture 2) and other levels of details (picture 3). Boxology was considered reductive, rightly so, at it was impossible to render visually the whole complexity of the nervous system in one figure, easy to read. Reducing it to one interactive interface may be more efficient but still reductive (as in here). How can you integrate such parallel topics as archaelogy, philosophy, art and functional imaging data in the same interface? If Alan was able to solve the representation of complex humanitarian disasters with his program, it may just be a matter of time for neuroesthetics.

As Alan showed it, this can be very useful when dealing with acute war or humanitarian crisis, where lots of information of diverse nature, format and source need to be rapidly and smartly processed in order to be presented in a visually integrated and useful way. A visually accessible summary can come in handy in specific situations (see this short video presentation of SensePlace2 a as an example).

This is about applying design, geography, and computer science to efficient understanding of complex situations, using a visual interface. Could we apply the same method to the headache of neuroesthetics? Could we have a visualization of the brain functional anatomy (topographic map of the brain), built on our current knowledge, integrating the inputs from all the other cross disciplines that relate more or less to the topic (anthropology, design, art etc...)? We could call that "the visual map", or "the artistic map", or the "seeing and knowing map".

When I learned Neurology in the early 1990s, we used the term "boxology" to pejoratively qualify a visual way to understand and explain how the central nervous system works. Below are three "boxologic attempts" to represent the complexity of brain functioning (pictures 1-3). Which one do you find the most efficient? Likely the first one, which is simplified and where there is a map (of the brain) to support your understanding. At the same time it lacks the biological or cellular levels (picture 2) and other levels of details (picture 3). Boxology was considered reductive, rightly so, at it was impossible to render visually the whole complexity of the nervous system in one figure, easy to read. Reducing it to one interactive interface may be more efficient but still reductive (as in here). How can you integrate such parallel topics as archaelogy, philosophy, art and functional imaging data in the same interface? If Alan was able to solve the representation of complex humanitarian disasters with his program, it may just be a matter of time for neuroesthetics.

This is part of a series of posts on the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics (September 2014).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed