Seeking salience: a short story about engaging art

William Seely

William Seely I learned from William that a philosopher can be truly polyglot; in this case, William speaks fluently neuroscience, art, and body language (not mentioning philosophy), and combines them brilliantly. The trick is, with my preconceived idea of philosophy talks, I was initially expecting a lengthy wordy presentation. It ended up being way more arduous and multidisciplinary than I thought. It took me some time to adapt to the superimposed messages and the amount of visual information present in his slides. But when I managed (more or less...), I found his presentation really interesting and relevant to the subject of SEEING and KNOWING.

William explained the notion of fast response latencies: the knowledge of basic attributes (such as the structure or function of objects) is integrated very rapidly into perception. In parallel, there is a competitive process by which attentional circuits bias perceptual processing to diagnostic features. Selectivity is a strategy to make us allocate limited perceptual resources to this or this component, on the fly (=instantaneously). He gave the example of the painting Guernica, by Picasso, to show how categorization (KNOWING) can affect our way of looking (SEEING): if we look at Guernica as a cubist painting versus a representation of a village bombed in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War, we perceive it differently. Try it (below): you may feel that in the first case, the impression is quiet, while in the second case, it is violent.

William explained the notion of fast response latencies: the knowledge of basic attributes (such as the structure or function of objects) is integrated very rapidly into perception. In parallel, there is a competitive process by which attentional circuits bias perceptual processing to diagnostic features. Selectivity is a strategy to make us allocate limited perceptual resources to this or this component, on the fly (=instantaneously). He gave the example of the painting Guernica, by Picasso, to show how categorization (KNOWING) can affect our way of looking (SEEING): if we look at Guernica as a cubist painting versus a representation of a village bombed in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War, we perceive it differently. Try it (below): you may feel that in the first case, the impression is quiet, while in the second case, it is violent.

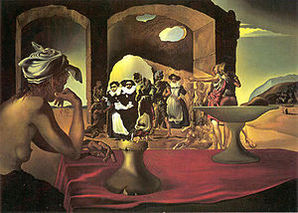

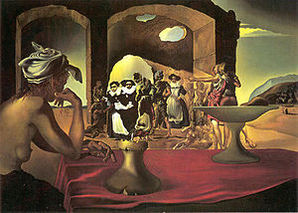

I also learned from William that if you push the concept a little further, playing with categorial mismatch can be funny. And here is an example of how a surrealist painter (Salvador Dali) used categorial mismatch to please the viewer in his painting Slave market with the disappearing bust of Voltaire (below), in 1940. Look at the first image, and think that Voltaire is in it. Then look at the the second, and think that the painting represents people all over the place. By KNOWING what you are looking for, you are SEEING differently.

I am tempted to apply William's demonstration to my own perception of his presentation. For example, when William said, in the middle of many other sentences: "categorization can change the diagnosticity of perceptual cues": how did I allocate my attention in the process of accessing and then perceiving his philosophical vocabulary, knowing that I categorized it right away as arduous and unusual to me, and that I categorized William as an a priori valuable speaker since he was invited to this conference? I think both categorizations hooked my attention and I processed it as something I want to learn more about. However this effect did not happened "on the fly" as he said, but rapidly progressively during his talk.

Then today, 10 days later, I realize that William may actually embody the multidisciplinary aspect of this conference. One thing for sure is that when I remember him speaking and jumping (conceptually and literally) from one concept to the other, and answering questions, I am thinking his response latencies must be extremely fast, indeed!

This is part of a series of posts on the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics (September 2014).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed