Le prince fourdroyé = the prince struck by lightning

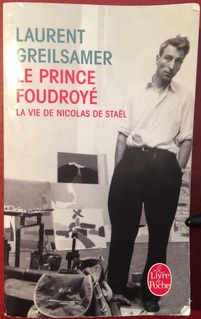

Le prince fourdroyé = the prince struck by lightning Navigating the spectrum between abstraction and representation is challenging. Semi-abstract paintings often feel nice, but also botched, incomplete, or irrelevant (see the zebra picture at the bottom of this post); but not the ones by my favorite painter Nicolas De Staël. Here is what I learned from De Staël's biography by Laurent Greilsamer (2003): making relevant semi-abstract paintings requires 3 artistic qualities: authenticity, idealism and ambition. De Staël’s artistic quest genuinely went beyond the classification of abstraction versus representation. Semi-abstraction happened without him categorizing it as such.

The authenticity of De Staël is palpable throughout his writings and his life. He was in remote contact with contemporary artists who were leaders in abstraction (ex: Kandinsky, Picasso) and criticized the very notion of categorizing abstraction versus figuration (see here). Originally influenced by Alberto Magnelli, pioneer in abstraction who went himself back and forth between figuration and abstraction, De Staël explored abstraction and then refused to aim specifically for it, exasperating his peers by his resistance to fully embrace the movement, and growing isolated: “You are stopping halfway, harshly reproached Jean Dewasne, who was resolutely turning towards geometrical abstraction” (p237). De Staël persisted his idealistic quest towards the “truth’, dedicating his entire self to it, neglecting his comfort and the one of his family “He is starving, and his family along him, but covers his canvas with the most sumptuous pastes” writes Greilsamer (P199). De Staël’s ambition for himself included high expectations for the art of painting in general. When Jean Dewasme, offended by the resistance of De Staël to embrace the notion of abstraction, asked him: ”One need to move forward, steam ahead, invent, invent everything, find new forms, not repeat the past!” De Staël answered: “What do you think I am doing? What matters is the painting, only the painting, the tension that happens there, between inorganic order and organic disorder! Voilà! One need to struggle with the canvas, make it go off!" (p237). As Greilsamer put it: “Staël followed deep reasons that were related to his pride, his confidence of being unique, his refusal of schools of thought. He preferred being the only contemporary artist in a “small” gallery, over being a pawn in a prestigious racing stable”. I think these were the driving forces that made De Staël mastering semi-abstract art, without naming it. The paintings below are the living proof of his mastery, in the 3 main genres of paintings.

The authenticity of De Staël is palpable throughout his writings and his life. He was in remote contact with contemporary artists who were leaders in abstraction (ex: Kandinsky, Picasso) and criticized the very notion of categorizing abstraction versus figuration (see here). Originally influenced by Alberto Magnelli, pioneer in abstraction who went himself back and forth between figuration and abstraction, De Staël explored abstraction and then refused to aim specifically for it, exasperating his peers by his resistance to fully embrace the movement, and growing isolated: “You are stopping halfway, harshly reproached Jean Dewasne, who was resolutely turning towards geometrical abstraction” (p237). De Staël persisted his idealistic quest towards the “truth’, dedicating his entire self to it, neglecting his comfort and the one of his family “He is starving, and his family along him, but covers his canvas with the most sumptuous pastes” writes Greilsamer (P199). De Staël’s ambition for himself included high expectations for the art of painting in general. When Jean Dewasme, offended by the resistance of De Staël to embrace the notion of abstraction, asked him: ”One need to move forward, steam ahead, invent, invent everything, find new forms, not repeat the past!” De Staël answered: “What do you think I am doing? What matters is the painting, only the painting, the tension that happens there, between inorganic order and organic disorder! Voilà! One need to struggle with the canvas, make it go off!" (p237). As Greilsamer put it: “Staël followed deep reasons that were related to his pride, his confidence of being unique, his refusal of schools of thought. He preferred being the only contemporary artist in a “small” gallery, over being a pawn in a prestigious racing stable”. I think these were the driving forces that made De Staël mastering semi-abstract art, without naming it. The paintings below are the living proof of his mastery, in the 3 main genres of paintings.

As an illustration, the 2014 Ikea catalog proposes ready-to-hang pictures that range from abstract (left) to representative (right). In the abstract picture (left), the design is nice but meaningless -to "look trendy". In the representative picture (right), the overwhelming subject matter (=the Eiffel tower) prevents you from appreciating any abstract qualities. In the semi-abstract picture (middle), the subject matter is quickly recognizable (a zebra) but the zooming, framing and black and white stripes add some abstract visual qualities that make the picture more interesting than a plain zebra. However, is it a relevant semi-abstract photo? I don't think so. It lacks authenticity, idealism and ambition (other than commercial).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed