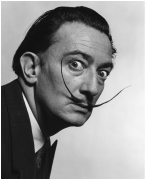

Dali’s Mustache, photo by Philip Halsman, 1954

Dali’s Mustache, photo by Philip Halsman, 1954 Some painters, as Salvador Dali, trick us. When we look at Dali's paintings (see picture below), we think we are looking at visual arts, while in fact, we are spying on Dali's mental world, highly loaded with thoughts and verbal concepts, not with visual concepts.

Salvador Dali used the visual language, not for the sake of it, but to illustrate his psyche, his favorite subject matter. When I visited the Dali exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2013, I could see how people were hooked as they accessed Dali's very unusual mind through his numerous art pieces. They were fascinated by Dali's exceptional mental giftedness, his overflowing delusional paranoia, and the fair amount of death and pornography included in his work. I was myself almost under the spell.

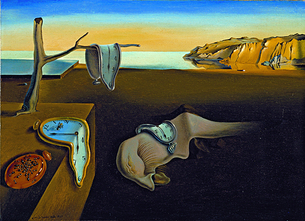

Dali is undeniably an amazing painter, at least technically. In fact, his technical virtuosity is so overwhelming that, at first sight, one may think it is what his paintings are about. The technical qualities of his paintings (smooth finish, pseudo realistic rendering) and the unusual subject matter (projection of the mind, melting watches, organic forms of unclear origin, surrealistic world) are what makes us believe that this is great visual art. But it is masking the reality, which is that Dali’s paintings are actually about the verbal concept of “paranoiac knowledge”, as he called it, or "the ability of the brain to perceive links between things which rationally are not linked", and not about the painting itself. Dali described his work as a "spontaneous method of irrational knowledge based on the critical and systematic objectivity of the associations and interpretations of delirious phenomena." His subject matter is his psyche. His process is based on psychological introspection. One could almost say Dali paints from imagination (as opposed to nature). The painting is just a support to deliver his concepts.

For example, in The persistence of Memory (see picture below, on the left), the notion of hard versus soft, the symbol of the time that passes, and the oniric or delusional imagery refer to verbal concepts issued from Dali's mind. The soft central piece may even be seen as a symbolic representation of the artist's tortured mind, half sleeping or delusional. In that sense, Dali's painting virtuosity takes us where he wants us to go, which is inside his complex mind. For that reason, one could consider him a brilliant, efficient painter.

Salvador Dali used the visual language, not for the sake of it, but to illustrate his psyche, his favorite subject matter. When I visited the Dali exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2013, I could see how people were hooked as they accessed Dali's very unusual mind through his numerous art pieces. They were fascinated by Dali's exceptional mental giftedness, his overflowing delusional paranoia, and the fair amount of death and pornography included in his work. I was myself almost under the spell.

Dali is undeniably an amazing painter, at least technically. In fact, his technical virtuosity is so overwhelming that, at first sight, one may think it is what his paintings are about. The technical qualities of his paintings (smooth finish, pseudo realistic rendering) and the unusual subject matter (projection of the mind, melting watches, organic forms of unclear origin, surrealistic world) are what makes us believe that this is great visual art. But it is masking the reality, which is that Dali’s paintings are actually about the verbal concept of “paranoiac knowledge”, as he called it, or "the ability of the brain to perceive links between things which rationally are not linked", and not about the painting itself. Dali described his work as a "spontaneous method of irrational knowledge based on the critical and systematic objectivity of the associations and interpretations of delirious phenomena." His subject matter is his psyche. His process is based on psychological introspection. One could almost say Dali paints from imagination (as opposed to nature). The painting is just a support to deliver his concepts.

For example, in The persistence of Memory (see picture below, on the left), the notion of hard versus soft, the symbol of the time that passes, and the oniric or delusional imagery refer to verbal concepts issued from Dali's mind. The soft central piece may even be seen as a symbolic representation of the artist's tortured mind, half sleeping or delusional. In that sense, Dali's painting virtuosity takes us where he wants us to go, which is inside his complex mind. For that reason, one could consider him a brilliant, efficient painter.

However, I would argue with that. The fascination comes primarily from the character of Dali himself (and therefore his subject matter), more than from the painting qualities per se. In a way, I wish Dali used his technical talents to make amazing paintings, meaningful in a plastic way, instead of limiting himself to illustrations of his mind. In his smartness, and untreated madness, Dali was in fact very aware of that: in a famous interview, he claimed he was a very bad painter and attempted to explain why (see video below).

Coming from a person with an oversized ego, this statement meant a lot. In the video, Dali was paradoxically humble (or realistic) about his work as a painter, and confessed he was mostly interested in the mind (being intelligent), while he felt paint should be restricted to dummies. This is where he really missed the point. Great art work as by Velasquez (that he quotes, see picture above on the right) are not necessarily made by dummies. In fact there are innumerable examples of great artists with a brain at least as gifted as Dali, but probably more psychologically balanced.

As a brain specialist, I don't grow tired of watching Dali's interviews and paintings: what an amazing window into the brain of a true paranoiac (or a person faking it very well), who fully embraced his delusions and made something remarkable out of it! Unfortunately, I think Dali teaches us more about paranoia than about painting. He had a great painting potential, but did not develop it. In a way he wasted his talent as a painter, because he was so focused on putting it at the service of illustrating his delusions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed