Figure 1: Sargy Mann in his studio

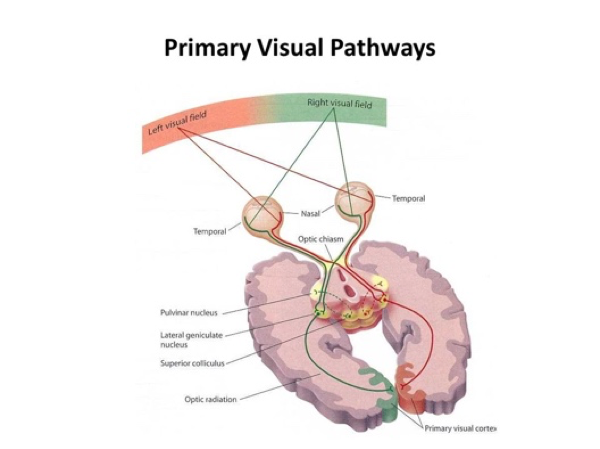

Figure 1: Sargy Mann in his studio Pablo Picasso once said: "Painting is a blind man's profession. He paints not what he sees, but what he feels, what he tells himself about what he has seen." On March 5, 2019, I attended a debate at the Royal Drawing School in London, about the late work of the blind British painter Sargy Mann (1937-2015) (Figure 1). Blind painters such as Sargy Mann teach us about perception. The debate reminded me that perception connects all our senses -including the visual, that there are multiple ways to perceive visually and therefore, multiple ways to produce and appreciate visual art.

Sargy Mann developed cataracts from the age of 35. At the age of 42, he got retinal detachment, in one, then both eyes, causing progressive degradation of vision. He eventually lost his sight in 2005, acutely, by his 68th birthday. He continued to paint for 10 years until his death.

As a painter, Sargy observed some changes in the process of losing his vision, that pertained to subject matter, color, details and authenticity (Figures 2A and 2B). Originally a landscape painter, as he became blind, figures became increasingly important. He explained: "Because I couldn't see people anymore it became more important to paint them." His wife Frances became his favorite model: " I suppose you always paint the things you most want to see." He carefully documented the other changes he observed in his writings (Perceptual systems, an inexhaustible reservoir of information and the importance of art). For example, he noticed that he "started using color in a much more intuitive and decorative way." He also noted that "the extraordinary paradox is that going blind has taught (him) to see more and differently". Finally, he talked about how blindness led him to more authenticity: "When I started going seriously blind that option of going out and finding Monet’s subject wasn’t there, and because I was so thrown back on my own limitations, curiously, I think this led me into a much more personal world, a world that was more my experience and my way of responding to it."

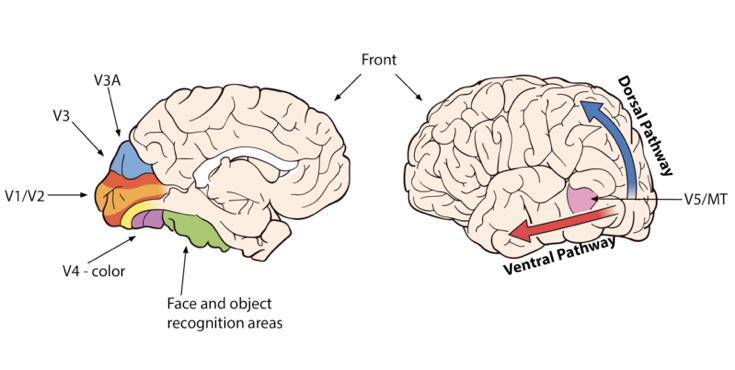

Semir Zeki emphasizes that he is interested in how the brain works in "the common man", not specifically in artists or art historians with highly trained brains. We can still learn a lot from Sargy's experience as a blind, experienced painter. He learned for years how to paint not only what he was seeing, but what he was experiencing. "If your subject is your own experience, as long as you have an experience, you have a subject. That has turned out to be true, even in total blindness." he said. Sargy described in great details his experience as a blind painter. For example, he explained how he could see colors right after he became totally blind: "I put ultramarine on a brush and painted the top right hand corner of the canvas and I had one of the most extraordinary sensations of my life. I saw the canvas go blue. It wasn’t a projection, it wasn’t me remembering what it was like, it was a percept for sure, but a percept clearly created somewhere in my visual cortex." Clearly, Sargy could access his inner visual perception, while being blind. He could see with his brain, not with his eyes.

People can even start painting after becoming blind. This is the case of John Bramblitt (Texan artist, born 1971), who became blind because of a problem in his brain, not in his eyes (Figures 5). He developed cortical blindness between his teenage years and the age of 30. This condition affects his occipital cortex, and therefore his processing of visual information and rendering of perceived image in his mind - his actual eyes are normal. He can't see colors or shapes and when he perceives light, it triggers an uncomfortable, non-visual, impression. He was a draftsman before becoming blind, had taken classes in drawing and illustration, which probably trained his visual system: " I did not start painting until after I lost my eyesight -- drawing and illustration though were incredibly important to me."

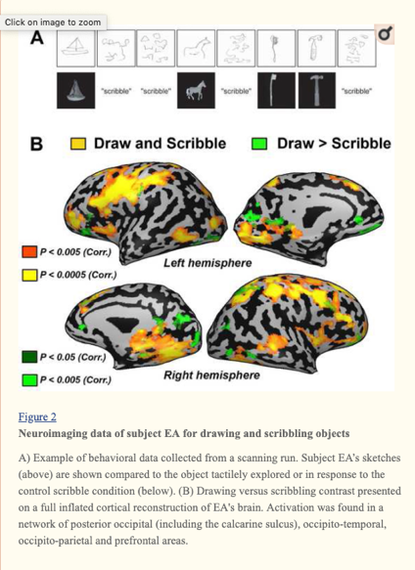

Eşref's tactile, spatial and visual giftedness drew the attention of neuroscientists who analyzed his brain activity while drawing an object he just felt with his hands, versus scribbling randomly, in an MRI machine (Figures 10 and 11). They found that the activation pattern in Eşref's brain while drawing shared similarities with sighted painters: the activity in fronto-parietal regions "may correspond to transformations from perception to two-dimensional image production and to the complex sensory-motor coordination needed for drawing". Most remarkably, areas specifically involved in visual perception, such as the primary and secondary visual areas in the occipital cortex (corresponding to mid and peripheral visual field perception) were also activated in this blind painter (Neural and behavioral correlates of drawing in an early blind painter: A case study, Amedi et al, Brain Res. 2008 Nov 25; 1242: 252–262) (Figures 10 and 11). While this brain activation pattern may be engaged in proficient braille readers when they "read with their hands", Eşref is not one of them. These regions are also engaged during tasks of verbal memory, but in Eşref's case, they were barely activated during the recollection of the object, only during the drawing phase. This suggested that drawing, informed by touching, was able to engage typical early visual circuits while shortcutting optical input in Eşref's brain: the artist's brain was able to see with his touch. It is unclear how Eşref was able to acquire this remarkable ability. But this study demonstrates that the brain has the ability to learn from scratch how to see based on tactile and verbal inputs only (not optical). These findings reinforce the notion of transmodal brain plasticity (sensory inputs are interrelated ), very robust in Eşref's case. As Alvaro Pascual-Leone, one of the authors of the study, put it: reversibly, "when we see a cup, we are also feeling with our mind's hand. Seeing is as much touching as it is seeing (...) but we may be more unaware of (seeing with our touch)."

If we look at art history, Monet went through a similar process of visual loss when he painted the waterlilies at the end of his life, with bilateral cataracts that modified color perception. He, too, used oil paint by memory (memory of the way colors looked like in nature and memory of the way colors were positioned on his palette). However, to my knowledge, he never used tactile input. Instead, since he was still able to perceive light, colors and shapes, but in a less detailed way, he enlarged his canvas to accommodate his visual needs, and finished his paintings in the studio, working from his perceived memory rather than directly from nature. As Sargy would have put it, Monet painted his visual experience (would I dare calling this his visual impression?!). This may explain why the waterlilies canvases are so large, a bit fuzzy and very blue.

In general, painters with no visual impairment often paint their visual "experience", too. Salvador Dali, for example, was particularly aware that his subject matter was a mix of his personal visual and psychological perception of reality. He even gave it a name: "paranoiac knowledge". His paintings may provide a realistic first impression (ex: perspective, everyday objects), but they are mostly the illustration of his inner world -his experience.

The question of differentiating the "real" world, from the "perceived/inner world" and the rendering of the world through art, has been unresolved for centuries. In the Allegory of the Cave (in Republic (514a–520a)), Plato suggested that only philosophers are able to perceive the "true" reality (the objects passing in front of the cave), while the prisoners (aka: the rest of us), chained to the wall of the cave, in front of the fire, only see a projection on the wall of the shadows of the objects passing by (Figure 12). In Plato's cave, would blind artist's paintings be categorized as a representation of the real objects or the projected shadows?

Plato suggested that the human condition is limited by the way our senses perceive reality (shadows of the objects), hiding the world of pure form, pure fact from us (the actual objects). He implied that the world of pure form is different and more valuable than the world of perceived reality. In the case of blind painters, I would argue that, on the contrary, the artists' senses enabled them to see reality in a more accurate, pure way. Sargy said he saw "more" and in a more authentic way. John says he sees things in more details and in a more felt way. Eşref also thrives at rendering his drawing quite representative of the reality, despite the absence of exposure to centuries of visual art.

Plato also suggested that if philosophers are able to escape the cave and see real objects under the real sun, major artists will continue to project the shadows of puppets with the fire light (aka the human made light) on the wall in front of the rest of us, bound to the cave forever. I don't think that Sargy, John or Eşref apply any filters between the reality and the viewer, as do artists in Plato's cave, since they don't have access to visual reality at the first place. Instead, they project their reality on the canvas, and this reality is as absolute and real as Plato's one: "In the 25 years of worsening sight before total blindness, because of the continual deterioration of the anatomical part of my visual system, I had to make enormous demands on the brain part, the visual cortex, in order that I should go on accessing some of the more — the infinitely more — of reality, that was still available to my depleted eye." said Sargy.

References regarding Sargy Mann

http://sargymannarchive.com/

https://www.cadogancontemporary.com/artist/sargy-mann/?section=video

Article in The Guardian:

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/nov/21/sargy-mann-blind-painter-tim-adams

References regarding John Bramblitt

https://bramblitt.com

https://www.boredpanda.com/blind-painter-john-bramblitt/?utm_source=google&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=organic

Documentary:

https://vimeo.com/87906998

Interview "Art if transcendence":

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mrEFcp6A5Ig

References regarding Eşref Armağan

http://esrefarmagan.com/

https://vimeo.com/33488357

Scientific article:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4518845/

Article in the New Scientist:

https://esrefarmagan.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/New-Scientist.pdf

RSS Feed

RSS Feed