Georges Perec

Georges Perec

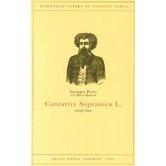

Georges Perec Georges Perec In 1974, Georges Perec, the French novelist of the Oulipo Group, wrote a hilarious pastiche of a scientific article about music: Experimental demonstration of the tomatotopic organization in the Soprano (Cantatrix sopranica L.). This parody is doubly relevant to neuroesthetics: its subject matter is a neuroesthetic study (how does throwing a tomato at a soprano affect her singing!), and the text itself is a masterpiece of language experimentation (pseudo-scientific article) by a virtuosic writer who was exposed to scientific literature when he was a librarian. The comic effect in Cantatrix sopranica L. comes from the paradoxical distancing of the author (serious tone) from his and our emotions (laughter), and the use of abstruse vocabulary and syntax contrasting with the so-called straightforward scientific demonstration that they are meant to convey. At the same time, those who, like me, published or tried to publish articles in scientific journals, will recognize the mindset we are in when it comes to (re-re-re-)write and (re-re-re-)format a manuscript for submission, in a desperate attempt to fit in and please the reviewers. The language used in scientific articles has always puzzled me. At the same time, when I am in a good mood, I find the autonomous flow of technical words, the regular recurrence of specific terms of unclear significance that become more and more familiar throughout the text, the rhythm chopped up by references, and the unreadable figures supported by overloaded legends, almost endearing, if not poetic. Cristina Grasseni reported an unexpected appreciation of beauty through "skilled vision"; why not acknowledging that "skilled scientific writing" may also carry an inherent aesthetic value? Yet I find the format of scientific writing very limiting in terms of creativity. In 2012, Phillip Prager, who spoke at the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics, suggested in his article "Making an Art of Creativity: The Cognitive Science of Duchamp and Dada" (Creativity Research Journal), that scientists are less resistant than artists to the idea of creativity as a "combinatorial process" that can be the result of chance: "seemingly incompatible concepts are blended into surprising new meanings, ‘‘a cut and paste process’’ in which ‘‘two concepts or complex mental structures are somehow combined to produce a new structure, with its own new unity (...) or ‘‘conceptual combination’’". Prager refers to scientific discoveries that date mostly from last Century (ex: unexpected discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928). I wonder if "chance" is still embraced today as a factor of creativity in scientific research, especially in academia? Where is the space for creativity, chance and combinatorial process in scientific articles? Similarly, this question applies to scientific grant applications: guidelines suggest that they be strongly "hypothesis driven", with a clearly defined "aim", and preliminary data (supporting the hypothesis) are a pre-requisite. More specifically, the NIH recommends, when it comes to designing a project for RO1 grants (classic research grants for principal autonomous investigators): "Be innovative, but be wary" or "Since innovation is a review criterion, you want to think outside of the box—but not too far". According to the NIH, innovation is a slight expansion of the "known" towards the "unknown" (see picture below). There is no space for chance, and barely for risk. So I am wondering and hoping: could neuroesthetic research (and emerging literature) be innovative and free itself from the sole constraints of academic standards? Could the emerging neuroesthetic literature be more open to chance? Wouldn't it foster creativity in the field? I hope so, but there may be a long way to go: Phillip Prager told me he was not able to publish his paper in an "art history" journal, while a more "scientific journal" accepted it right away. Still, when I read his article, I did not find it really... scientific (nor do I think that Creativity Research Journal can be considered a pure scientific journal)! Regardless, I found his article absolutely fascinating and relevant to both science and the history of art.

1 Comment

I created a Proust Questionnaire on Neuroesthetics (inspired by the original -and more romantic! Proust Questionnaire). It is a nice ice breaker and promotes interdisciplinarity. A few of us tried it already (click on the icons below). What would you answer? You are welcome to try it: it takes 3 minutes. Proust Questionnaire on Neuroesthetics

3 extra questions related to the International Conference on Neuroesthetics:

This is part of a series of posts on the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics (September 2014). I listed the 16 speakers of the conference. Click on my sketches to read my posts, some of them include interviews. Or scroll down my blog. Click here to read the interview of Tamia Marg, President of the Minerva Foundation

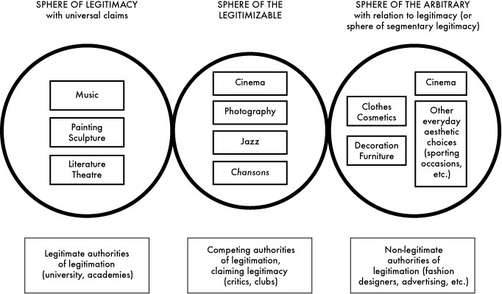

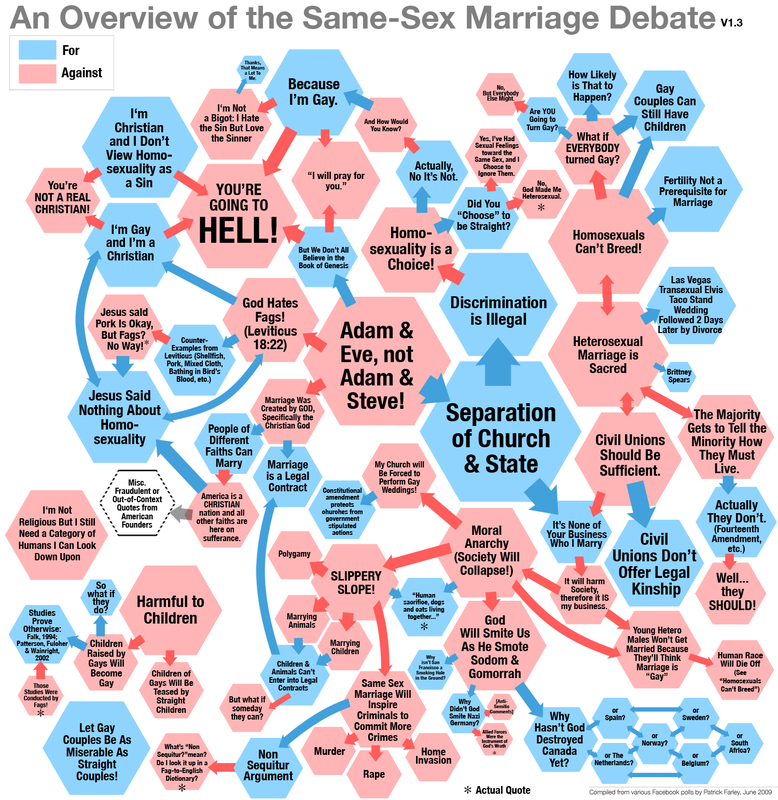

Introduction  Johanna Drucker Johanna Drucker Johanna put together the agenda of the conference this year. I counted 13 areas of expertise for 15 speakers! Communication, neurosciences, computer sciences, archaeology, art, anthropology, design, information science and technology, psychology, philosophy, history of art, private sector, and aesthetics. I heard two opposite types of comments: an artist suggested there should be more artists talking about the visual essence of their work (not "rational art"), while a scientist was hoping for presentations with less words and more data to chew on. I am thinking: what about joint presentations for next year? This would be the ultimate ice breaker between disciplines. And that is what I am the most interested in. Talking about building bridges: during his presentation, Aaron Marcus suggested that design ethics should be mandatory in graphic design schools. Later, at the end of the conference, Jessica Ferris incisively questioned what differentiated her work as a performance art director, from shooting a marketing commercial, since in both cases the (visual) tools used to convey the message or please the audience, were universal and thus similar. I had the same question regarding painting: what makes it different from graphic design? I think meaning is what differentiates art from design, and ethics is needed in both. That could be a topic for the next conference: meaning / ethics of the visual language. I foresee endless controversies and animated joint presentations! This is part of a series of posts on the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics (September 2014). Cognitive Neuroscience of aesthetics Marcos Nadal Marcos Nadal I learned from Marcos that the field of knowledge in neuroesthetics has been increasingly growing over the past few decades, especially since we agreed that there is no SEEING without KNOWING. The notion of the viewer becoming an active perceiver (organizing agent, Gestalt psychology) rather than a pure visual recipient (empirical esthetics), and then the concept of Inner Vision by Semir Zeki grounded the way to modern neuroesthetics. As he said, Marcos is mostly interested in aesthetics as a way to appreciate "beauty" (as opposed to a more global and formal definition of aesthetics). The data he presented suggest the influence of expertise, culural references, or context on the appreciation of beauty, documented by neuroimaging. For example, Marcos showed that the neurological pathways are diverted when viewers look at a picture of art they are told was authentic versus fake, or when a sponsor logo is copied next to the image (especially if the viewer was a non-expert). I put Marcos' observations in relation with two other ways to look at the influence of the contemporary and historical contexts on art production: art and sociology. Almost a century ago, Wassily Kandinsky stated, in The Doctrine of Internal necessity, that: "Inner necessity originates from three elements: (1) Every artist, as a creator, has something in him which demands expression (this is the element of personality). (2) Every artist, as the child of his time, is impelled to express the spirit of his age (this is the element of style)—dictated by the period and particular country to which the artist belongs (it is doubtful how long the latter distinction will continue). (3) Every artist, as a servant of art, has to help the cause of art (this is the quintessence of art, which is constant in all ages and among all nationalities)." Kandinsky here uses a very different language from Marcos to basically express the same overarching theme: the artist depends not only on himself, but also on the contemporary context he lives in and the history of painting. I find it fascinating to establish such a direct parallel between the neuroscientific and the artistic approaches. More recently, Pierre Bourdieu approached the interactions between culture and the production of art with a sociological eye (The Field of Cultural Production (1993) and The Rules of Art (1996)). For example, he categorized the legitimacy of various types of art production depending on who defines it, from academia to "non legitimate" authorities such as advertising (see picture below). These observations put another light on the influence of culture and context on art, again complementary to Marcos and Kandinsky. I could go on an on, and look at how to address the same question with an archaeologic or an anthropologic eye... The influence of culture (contemporary and historical) on vision could be a great theme in itself for a future International Conference on Neuroesthetics! This is part of a series of posts on the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics (September 2014). Key principles of visual semiotics, visible language, user-interface and user-centered design Aaron Marcus Aaron Marcus I learned from Aaron that one can apply visual semiotics to as many fields as possible. His team "helps people make smarter visual decisions faster for any technology platform content". They invented the concept of the "machines" with an endless list of application domains - the green machine, the health machine, the story machine, the driving machine etc. The design is done, the coding needs to be done. What I found the most interesting in Aaron's presentation is the discussion he initiated about the ethics of design. I actually wonder: the absence of intellectual property makes Aaron's design projects noble in a way, but does it make them ethical? Is the concept of any kind of "machines" ethical? I read George Orwell who anticipated that Big Brother would be watching us in his anticipation novel 1984; when the book was published in 1949, the idea of some entity monitoring our private life not only sounded un-ethical, but also politically scary. More generally, I wonder whether ethics is to design as meaning is to art (see my similar reflection in this post)? Are designers or neuroscientists walking on slippery grounds when they play with ethical boundaries (see the end of my blogpost on the work of Aude Oliva)? Are artists welcome to cross the line if this is meaningful in their artistic process? The performing artist Robin Williams seemed to believe so: he considered himself performing "legalized insanity", meaning crossing the line deliberately and repeatedly; check his highly visual, convincing and hilarious description of the process in the first minute of this video. Ethics and meaning are obviously controversial topics, and I would hate to suggest that painters have no ethics and designers no meaning! But that could be a great overarching theme for a future International Conference on Neuroesthetics. This is part of a series of posts on the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics (September 2014).  Peter Wells Peter Wells I learned from Peter that it is hard to keep what I learn secret. Indeed, Peter requested his presentation be not recorded or taped. As a matter of fact, I don't record or tape talks, but am good at taking notes and remembering. I can only tell you that his presentation was a great ending to the conference. We traveled back through pre-literate human societies, where there was less to see, especially less manufactured stuff. Peter showed us how visual design evolved on ornaments and potteries, to become increasingly linear. But I won't say more, Peter spoke of unfinished work and working hypotheses, and I respect that. However I can't resist to include a link to the gorilla experience on attention blindness by Simons and Chabris (1999): click here to try out (it takes a few minutes max and is very fun if you don't know the trick in advance). Peter referred to it at some point in his presentation, and it is very relevant to the theme of SEEING and (not-)KNOWING. This is part of a series of posts on the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics (September 2014). Seeing and knowing with the bride of Christ: How a metaphor shaped thought and action in the Middle Ages Line Cecilie Engh Line Cecilie Engh I learned from Line that metaphors car be used for "SEEING thoughts". Line read for us the story of the representation of marriage, between husband and wife, Christ and Church, or Christ and Soul, through the Middle Ages. She intended to explain how "bridal imagery produce cultural meaning" (and not vice versa) and, by extension, "how visual thinking can have political and social impact" -very relevant to the theme of SEING and KNOWING. Line took us on a lively and erudite journey though the representation of marriage in the Middle Ages. At the end I had the impression to have listened to a brilliant essay about marriage in general, that is still relevant to the time we live in. Look at all the pink bubbles on the right hand side representation of the contemporary debate of same sex-marriage: if I am following Line, most of them must be a consequence of the metaphoric approach of marriage in the Middle Ages -not that I want to engage a political debate on this subject on this blog. That being said, I liked that reflecting on neuroesthetic considerations such as "visual thinking", which may seem narrow and specialized at first sight, can actually be associated with such significant contemporary, political and social relevance. This is part of a series of posts on the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics (September 2014).

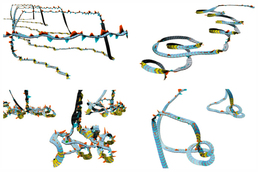

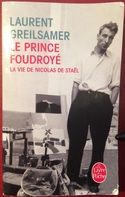

Seeing and knowing: Colin Ware looks for visual patterns in whales, could we try it in art?9/14/2014 Perceiving, interacting and computing: the process of thinking visually Colin Ware Colin Ware I learned from Colin that visual thinking design can be applied to all kinds of subjects. For example, Colin showed us his program called "Trackplot", that allows researchers to search for visual patterns of movements of tagged whales traveling in the ocean (picture 1). The system is much more efficient than the systematic and sequential visual analysis of each individual whale movement, and its comparison with each and all of the other whales. This is really about improving SEEING for better KNOWING, as in the presentation of Alan M. MacEachren. Design at the service of cognition is core in ACT-R, a cognitive architecture and theory for simulating and understating human cognition (picture 2). I wonder: is Colin's work applicable to painting itself (and visual arts in general, my favorite topic)? If we consider art history as a way to look at individual art productions and situate them within the wide contemporary landscape and tradition of painting, wouldn't the attempt of defining "-isms" (art movements, as in picture 1) share similarities with "trackplot"? After all, both search for visual and cognitive patterns in a jungle of visual data and knowledge. As a matter of fact, defining "...isms" and creating historical timelines of art movements help us figuring out what artists are doing. This is thereby, in itself, a project of visual cognition. I hypothetise that, by analogy, Colin could develop an alternative ACT-R based way to search for visual patterns in art works, that would be more efficient than using our retina to compare thousands of art works. At the same time, I can already hear the voice of a lot of artists, who couldn't disagree more, and would oppose categorizing visual art in such a simplified and automatized way. Nicolas de Stael, who would have celebrated his 100th birthday this year, had he not died prematurely in 1955, would be their best advocate. I just finished reading his biography (picture 3), where he consistently refuses to be categorized as an abstract (or a figurative) painter. In the late postwar 1940s, he claimed that, "realism is a silly nonsense, and "abstraction" (...) is self-evident since The Virgin of Fouquet, Fra Angelico fresco and Van Eyck paintings". "He would almost imitate Delacroix, when answering critics who qualified him as a romantic painter: "Me, sir? I am a pure classic painter..."" (p240, my translation). It means De Stael would have considered picture 4 a classic painting and picture 5 the origin of abstraction. My artistic eye understands and agrees with him. However, I am not sure you do! I checked: unsurprisingly, De Stael is not listed under any of the "classic" art movements in the "...isms" book (picture 1). In fact he is not mentioned under any categories at all, here or in the modern version of the book (picture 2). I doubt that a hypothetical artistic version of Colin's "Trackplot" could help here: recognizing visual and conceptual patterns in De Stael's work remains too controversial at this point! I won't start the debate around the definition of abstraction here, and I will comment on De Stael biography in an upcoming separate blogpost. However, this makes me reflect on the nature of art production as a personal experience, and on the challenging nature of transferring the artistic skilled vision, as Cristina Graseni would call it, into a software machine.

Developing intelligent enough tools to analyze art may sound like science fiction today. But it may just be a matter of time. In any case, I think it is never too late for artists resistant to technology to stretch their minds, look at how others are looking, fight "neurophobia" (as Semir Zeki describes it), and participate in the big neuroesthetic quest... maybe by starting with sharing their input for building a smart "artistic TrackPlot"! This is part of a series of posts on the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics (September 2014). What is the mission statement of the Minerva Foundation and how does this relate to the International Conferences on Neuroesthetics?

The Minerva Foundation, founded by my parents Elwin & Helen Marg in 1983, supports activities that advance our understanding of how the brain functions with a particular focus on vision. The International Conferences on Neuroesthetics started in 2002 with the encouragement and support of Semir Zeki and his Institute of Neuroesthetics at University College London. The intent of the conference is to allow a cross-pollination of scientists, artists and humanists speaking on a theme central to our sensual experience. I'd like to strike the right balance between obtuse technical jargon and inarticulate art, and reach both the lay and professional public. The 2014 conference was a success in that respect, though I would like to see more neurologists and neuroscientists attending— I believe the design of their research could benefit from exposure to perspectives from other disciplines. What is the mission of the Minerva Foundation, besides organizing the International Conferences on Neuroesthetics? The Minerva Foundation is involved in two other projects, besides the conference. Since 1985, the Foundation has awarded the Golden Brain each year to a promising or unsung investigator with promising research yielding significant findings in vision and the brain. And this year, we have developed an incubator program devoted to projects at the intersection of art, technology and science, challenging the separateness of those fields, under the leadership of Vero Bollow, Director of the Foundation. How come you have maintained free access to the conference? Do you plan to have it CME (Continued Medical Education) accredited, to attract more physicians? Keeping the conference free, allowing students, artists, as well as professionals to make up a diverse audience has its merits, there is no doubt. At the same time, offering a free conference paradoxically may make it appear less worthwhile. Plus, keeping it free limits the amount of resources that we could devote to other projects, including publicizing the conference. We have not thought about CME accreditation but that could be a good idea to pursue. Could you tell me how many people participated in the conference this year? Also, I was pleased to see a fairly balanced gender distribution in the audience, maybe due to the multidisciplinary approach, promoting diversity. Would you happen to know the percentage of women versus men, and the distribution of their expertise? It is hard to say what qualifications or proficiencies were represented among the audience or gender since we did not collect that information. In the future, we would like to get the word out more widely in advance so that the conference hall is filled to capacity. Do you think the 2014 conference went well? Did you enjoy it? Yes! it was very successful in my eyes. The panel was even more multidisciplinary than it has been in the past. And this is a direction I would like to see continue. Although the topic has not been chosen yet, I anticipate the next conference will not disappoint. This interview was reviewed and approved but Tamia Marg. This is part of a series of posts on the 11th International Conference on Neuroesthetics (September 2014). |

AuthorDorothee Chabas is a painter and neurologist Archives

April 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed